The ability for the knowledge of mankind to progress and develop is dependent upon people observing a phenomenon, investigating its cause and publishing their findings for others to see. Historically, back when literacy was in the hands of the few, and the distance over which knowledge could be transmitted was very short, it was difficult for somebody to be able to document a piece of knowledge and have it read by enough people to ensure it was transmitted down the generations.

Consequently, whatever it was that caused the small population of Mesolithic people who built

Stonehenge to do so is lost in the mists of time. Likewise, while ancient people could build complex machinery such as the

Antikythera mechanism as early as 150 BC, perhaps inspired by the work of Archimedes, the secrets of its purpose, design and usage were not passed on to others, meaning it was centuries before such mechanisms were possible again. If knowledge isn't written down and passed on to others, it runs the risk of dying out within a generation and setting back progress hundreds of years before somebody else comes up with the same idea.

Since literacy was traditionally only available to the elite or the hierarchy of the church, the common man was barred from being able to read others work or write down their own observations. In pre-modern times it is unlikely that literacy was found in more than about

30-40% of the population, meaning that 60-70% of people were out of the equation of book learning altogether. This was true in England as late as the mid-Victorian era before compulsory education kicked in.

For centuries, the only way for a book to be duplicated was for it to be laboriously copied out by hand by scribes, which mean that books were outrageously expensive and limited in number. It is said that the 17th century poet John Milton, although blind towards the end of his life, was the

last person to know everything because he had read virtually every book ever written at that time.

Given the small numbers of each book that existed,

on numerous occasions library fires wiped out every last copy of a given work. Consequently, the list of

lost literary works is long and harrowing, and who knows how much quicker knowledge would have advanced if those works had been duplicated and distributed before they were lost?

Then

Gutenberg invented moveable type in 1439, and the cost of reproducing books came down drastically. The number of books published in Europe ballooned, directly enabling both the Renaissance and scientific revolution:

So the simple ability to publish works dragged humanity out of the dark ages. Even then, the ability for a person to record and distribute their ideas was limited by having the financial resources to allot the time to write a book and the backing of a publisher to print and distribute it. That limitation was only overcome with the arrival of the Internet in the 1990s.

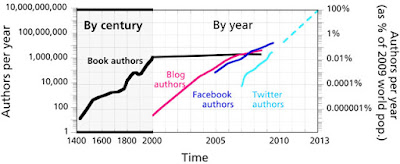

Nowadays, it's possible for anyone with access to relatively cheap computer equipment, or even a tablet or smartphone, to publish their thoughts to the entire on-line world. Social media allows tweets and statuses to be broadcast instantly around the world, free blogs like this one allow publication of longer thoughts, ideas and concepts and cheaply hosted websites allow grander schemes to be demonstrated to the world. The number of 'authors' can therefore be said to have ballooned well beyond traditional book authoring since the arrival of the Internet:

Now, clearly there's a question over whether more quantity necessarily means more quality, and quite a bit of internet content is limited to kitten pictures and smut. However, the number of people that a given on-line publication can theoretically reach is now heading towards 3 billion:

The fastest Internet user growth rates can be found in third world countries where access to education has traditionally been limited, reaching up to 17% growth per year in many African countries:

Since the first website went on-line in 1991 there are now a staggering

980 million websites out there:

Given that little lot, the chances of another John Milton reading everything that had ever been published are exactly zero. The democratisation of published knowledge has well and truly arrived.